While patients who must use medical devices might believe that the companies who manufacture them do so according to rigorous standards, this may not always be the case. Many organizations claim that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not test devices as thoroughly as they should, allowing them to come into the market.

Although medical devices extend and save lives, they can fail for a number of reasons, leading to medical complications, serious illnesses, and even death for some patients.

One well-known example is the ReShape and Orbera gastric balloon devices, which were approved back in 2015. The initial reviews were positive, claiming that the balloon devices were a good opportunity for people hoping to lose weight. Either one of the two devices would be inserted into the patient’s stomach through an endoscopic procedure that went through the mouth. Then, the balloons were filled up with saline to make them expand and fill up the stomach. An early trial with 255 patients produced positive results, with one showing an average of 21.8 pounds lost.

Several months later, news reports surfaced, claiming that several people had died, and the FDA had sent out on alert about the deaths. This alert claimed that they had updated physicians and told them to closely monitor their patients for risks of spontaneous over-inflation and acute pancreatitis.

One source claimed that there could be many more deaths. Adverse event reporting for medical devices is voluntary for doctors and patients but mandatory in the industry. Due to this, the FDA may not receive accurate data about patient complications and deaths related to medical devices.

Medical devices are regulated under different laws than drugs, which is why the standards are weaker. The Medical Device Amendments of 1976 allowed for certain risk-based review standards while encouraging innovation. Since then, corporate lobbyists have been working to have Congress make it easier for medical devices to get FDA approval by easing up on regulations.

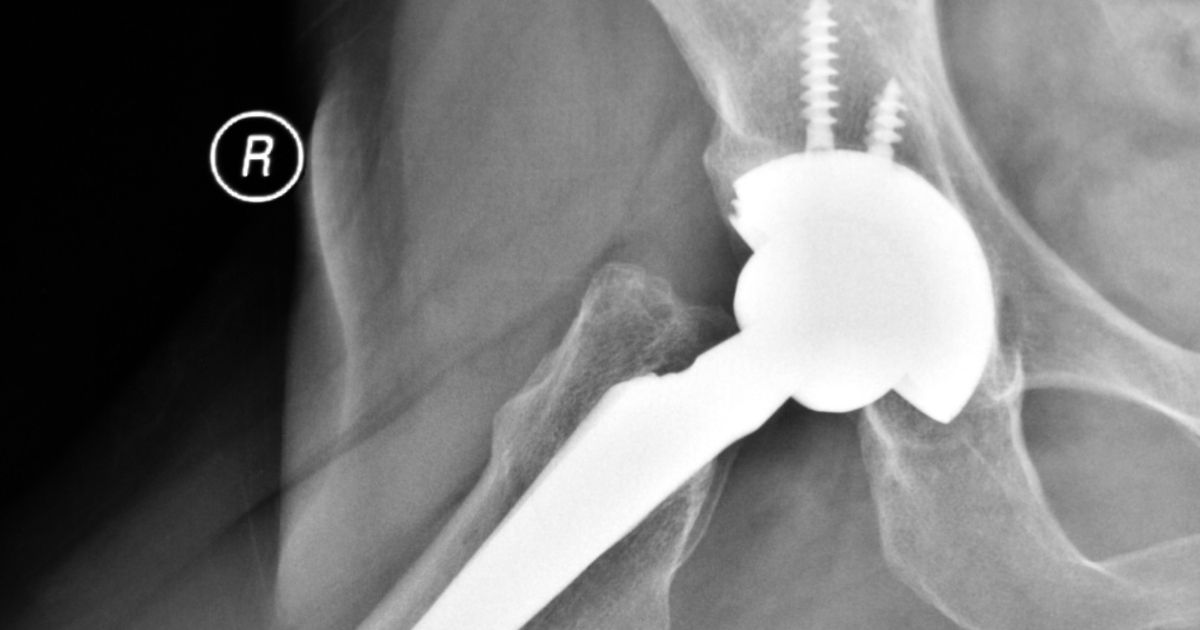

The category of medical devices is bigger than you might think. Medical devices include pacemakers, artificial hips, bandages, power morcellators, and even weight loss balloons. Here are the three main classes of medical devices:

Each year, the market for medical devices increases around 20 percent, and as this number grows, the approval process may be getting even more compromised. With all of these roadblocks, there does not seem to be a proven way to carry out detailed, purposeful, large-scale supervision and scrutiny for medical device functionality and safety. Without ways to report problems in a timely manner, it can take several years for people to become aware of defective medical products and safety issues. It is also thought that manufacturers tend to underreport device safety issues even when they do have the data.

Another problem is the FDA’s self-registration process, which allows manufacturers to misclassify their devices. A high-risk product could be misclassified as a Class II for example and would therefore not have to go through the kind of rigorous testing that Class III devices undergo. These companies have also been known to overstate the effectiveness of their medical devices in order to get them out to the market before their competitors.

The 2002 Medical Devices User Fee Act mandates the FDA to use a least burdensome route to device approval. Because of this, devices can be cleared for the marketplace without going through any patient trials. Others get by without demonstrating any efficacy or safety for patients. Congress has also approved certain measures that allow more devices to make their way through the process without oversight.

Even when medical devices go through scientific reviews, the standards for quality may be below par. Many of the studies are prone to biases because they are randomized, controlled trials are not held as often as they should. Instead, the FDA may settle for a reasonable assurance that a medical device is both safe and effective.

The litigation process for medical products liability cases can be complex. If you have been injured by a faulty medical device, contact one of our Philadelphia defective medical product lawyers at Brookman, Rosenberg, Brown & Sandler. Call us at 215-569-4000 or complete our online form to schedule a free consultation. Located in Philadelphia, we serve clients throughout New Jersey and Pennsylvania, including Delaware County, Chester County, and Philadelphia County.